Retiring after 32 years, Board Vice President wins Aiken Award

Longtime Washington Electric Co-op Vice President Roger Fox, of Walden, will step down from the Board of Directors this fall. For his service, Fox has been awarded the George Aiken Award, presented annually by the Northeast Association of Electric Cooperatives.

Fox has served on the Board for 32 years, but his involvement with WEC goes back to the early 1970s, when the Co-op strung a line out to Apocalypse Farms, which was the nickname of the Walden commune where Fox lived in the 1970s. Former WEC President Barry Bernstein, also an Aiken Award recipient, said that Fox deserves the honor for his active participation and dedication to governing the Co-op, and also as “one of the original group of Co-op members who got together in the early 70s to raise questions about the openness and direction of our owner-member Co-op.”

For his part, Fox appreciates many years working with “committed supporters of cooperatives to promote the public interest, and the specific interests of WEC members and other rural Vermonters.”

“I liked the idea of consumers collaborating in the commercial space.”

– Roger Fox

Going up the country

Fox was raised on Long Island in a family that shared interests in technology and gadgetry. He went to study engineering at MIT, which, he said, felt like an escape from the consumerist suburbs. “I had the chance to spend time with a lot of other nerds and assorted misfits,” he said. The Vietnam War, and the prospect of the draft, made a grim context for education and career decisions. Like a lot of his friends at graduation, Fox said, he tried to avoid enlisting in the armed services and found a deferrable job working on the Apollo project in the space program in Florida.

But before long, he was back in Boston, living with a former dorm-mate from MIT. Between the war and the mass protests that brought the war home, “it seemed like society was falling apart,” he said. So when his friend’s former girlfriend, a Goddard student, connected them with a piece of land for sale in Walden, they pooled their money and moved to the Northeast Kingdom.

“We had what we called a work commune, because that was popular terminology in those days, of six people,” Fox said, “friends of friends who were looking for adventure.” Apocalypse Farms was formed. How long it lasted, Fox said, depends on how you look at it. The winter of 1970-1971 was the snowiest on record in Vermont, and caused more than a few back-to-the-landers to change their minds. Fox recalled, “By the time the snow melted in Walden it was the middle of May.”

CoFEC

Fox’s only previous experience with cooperatives was with the famous Harvard Coop bookstore in Cambridge. But when he discovered Apocalypse Farms’ electric service would be provided by a cooperatively–owned utility, he was intrigued. “I liked the idea of consumers collaborating in the commercial space,” he remembered. The Public Service Board (as the Public Utility Commission was then known) had recently tightened regulations on line extensions to discourage overdevelopment. WEC told him they would extend a line out to the property if the commune built enough of a house to show they intended to finish it. So, Fox tells it, the group poured their own concrete foundation and built a deck over it with a gasoline generator and radial arm saw, and that was enough to warrant the extension. And the next year, in 1972, he attended his first Annual Meeting of WEC members.

“I was by far the youngest person there. I remember a sea of white hair,” he said. “It was a big social event, which it still is. You could get a free meal and hang out with your friends.” But, he said, there wasn’t yet much involvement from the back-to-the-land generation; the identity of the Co-op was traditional. Fox explained this as a natural lull: after WEC was formed in 1939 and lines were strung, “people were excited about having access to electricity for a while, but things settled down and they were having trouble finding people to serve on the Board. So it ended up being an insiders group,” he said. “The people who were on the Board had been on the Board for a long time.” While he credits them for keeping the Co-op operating, he said, he also didn’t see the cooperative structure being used to benefit its members.

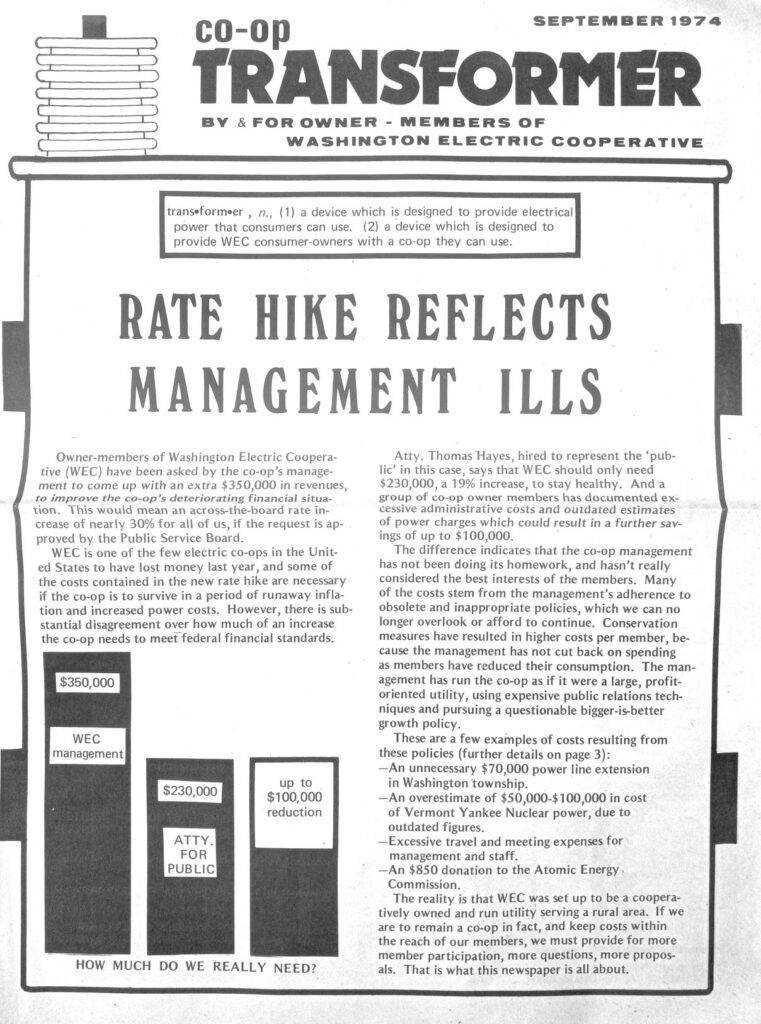

He knew enough about illumination to recognize a problem with WEC’s then-unstable voltage and the light bulbs provided by the Co-op: basically, WEC leaders didn’t let members know they were not getting their money’s worth from their light bulbs. Other friends were newly attentive to energy issues because of the oil embargo of 1973, and that sparked interest in Co-op policies. “There were a number of people who attended the 1973 members’ meeting who started giving Co-op management a hard time,” he said. “It seems to me there’s always been that tension between creatives or innovators who are thinking, ‘how do we solve long standing problems,’ as opposed to the sticks in the mud who think there are a limited number of approaches to dealing with a problem that would be considered acceptable.”

The innovators formed CoFEC: The Committee for an Effective Co-op. When they found Co-op Currents’ coverage insufficient, they printed their own rebuttal newsletter, the Transformer, and mailed it to all Co-op members. CoFEC ran a proxy campaign – back then, Fox explained, bylaws allowed for proxy voting at the Annual Meeting – and elected their slate of candidates to the Board: Tunbridge sheep farmer and philosopher Robert O’Brien, artist and helper Bob Fisher of Middlesex, and Barre politician and activist Margaret Lucenti. But in 1974, the Legislature – influenced, Fox said, by the “old guard” on the Board – authorized the Co-op to allow voting by mail. CoFEC was unable to seat another candidate until the late 1980s.

Courtesy Roger Fox.

Fox said he maintained a background role for the next several years and focused on his screen printing business: Apocalypse Graphics. With no engineering job prospects in the Northeast Kingdom, he turned to a skill he’d developed in the basement of his MIT dorm and became a printing entrepreneur. Early successes included a sold-out run of t-shirts for the 1973 Sugarbush Folk Festival and a contract for thousands of suggestive bumper stickers promoting milk. He’s also printed stickers for Vermont political candidates, garments for Vermont businesses and organizations, and his own line of farm-themed animal and vegetable t-shirts.

In the meantime, WEC was involved in the notoriously mismanaged construction of the Seabrook nuclear power plant in New Hampshire, whose cost overruns brought the Co-op and other utilities close to bankruptcy. “That was an issue that got people like me and Barry [Bernstein] and Don Douglas, who were still interested in reforming the Co-op, engaged,” said Fox. CoFEC-sympathetic Directors were a minority on the Board when he agreed to join a slate of candidates in 1991. All three won. With a new Board majority, WEC entered an era of environmentally progressive leadership that continues today.

Legacy

“We were early adopters of the value of environmental responsibility by electric utilities,” reflected Fox. Those achievements include getting WEC out of its contract with the now-defunct nuclear plant Vermont Yankee and replacing that power supply with landfill gas and wind, as well as advocating for adding public directors to VELCO’s leadership, to support accountability to ratepayers by the utility-owned statewide transmission utility.

Fox’s fellow Directors say his legacy also includes his attention to whistle-clean internal governance processes. He served as the “parliamentarian of the Board,” they co-wrote in his Aiken award nomination, ensuring compliance with Vermont laws and regulations, the Cooperative Principles, and WEC’s own bylaws and policies.

Collaboration and cooperation is the key to living in northern Vermont, he said. It bears on the Co-op because, he said, “we can’t be assured of the Co-op’s continued economic viability.” His analogy is that small towns facing economic stress, but not wishing to merge, could look for leverage points among their expenses – for example, work with the neighboring town to share the big machinery. WEC, he thinks, would be well served in a political and regulatory environment that allowed similar creative solutions.

But protecting local norms is the other half of that dime. Now at the end of his Board service, Fox senses friction in a future where transplant Vermonters, spurred here from denser locations by climate change and the prospect of working from home, expect too much. “I’m concerned that too many of our members aren’t aware of our Co-op’s history or the benefits it provides or is able to provide to our communities. It’s taken for granted. People have unreasonable expectations for what we’re able to do,” he said.

He continued, “I’m concerned about the impact high speed broadband is likely to produce in our area.” The ability to work from home stresses a housing market that’s already unaffordable for people who live here, he pointed out, and small communities are sensitive ecosystems. “It’s important to maintain some balance between the people who have some tenure here and the people who don’t have any tenure here but just showed up and want to influence local culture,” he said. “Seems more likely than not to impact Washington Electric Co-op.”

The timing of Fox’s departure means the Board may appoint a Director of their choice before the Annual Meeting in May 2024, when his term technically ends. By the 2024 election, the Director appointed to fill his seat will effectively be an incumbent. During past Board vacancies, Fox explained, the Board found that qualified members who were unwilling, at first, to run for election were willing to serve by appointment.

He plans to dedicate more time to his family and to many other projects. Fox still identifies as irrepressibly youthful and energetic, a carrier of the ideals that brought him to Vermont in the first place. The self-described young radical, at 76, has plenty still to accomplish. “I should make it clear I haven’t grown up,” he said.

| Interested in serving on WEC’s Board of Directors? |

|---|

| Contact President Stephen Knowlton with interest, c/o Rosie Casciero: rosie.casciero@wec.coop WEC aims to appoint one Director in 2023 to the seat vacated by Roger Fox. In the December-January issue, WEC will issue a general call for candidates to run for the 2024 Board election. |