Electrical safety tips from Safety and Environmental Compliance Specialist David Young

Underground Electrical Safety and 811 (DigSafe) – February 2025

When we think of our electric distribution grid, we talk a lot about “poles and wires.” But in some cases, electrical equipment is located on the ground and wires travel underground. Here’s an example: most WEC members have a transformer that resembles a gray can, located high on a pole outside their home. But some housing developments have what’s called a padmount transformer: in this case, the transformer is on the ground, usually housed in a greenish metal box, and the wire that carries electricity is buried underground.

Recently, up in the northern part of our service area, a private plow truck driver was unaware that a padmount transformer was in the path of his plow. When he drove into it, the damage caused the equipment to leak oil. This was close to a lake, so it became not only an electrical safety concern, but an environmental safety concern. With some awareness of ground-based electric equipment, the accident could have been avoided.

Padmount transformers require 10 feet of access in the front, and 4 feet around the side. Brush and vegetation should not be planted or allowed to grow right around them—although to many, it’s an ugly green box, so I understand efforts to improve aesthetics.

And here’s another story that really spooked me: I once patrolled a development where several padmounts needed vegetation cleared away. The last padmount transformer I came across was unlocked, and there were several matchbox cars in front of it. First: the padmount should never be unlocked, and second: nobody matchbox car-aged should be playing around any transformer. There are safety measures in place to prevent shock, but it’s far too risky.

So far we’ve just talked about what’s aboveground. Underground, there are live electric wires connecting your padmount transformer to your home, just like the wire that travels overhead from a pole-mounted transformer. 811, or DigSafe, marks the location of those wires. But you may also have propane lines, or other underground systems, that are unmarked: 811 only marks equipment that is utility-owned. Hire an underground locating company to mark your underground systems, and your aboveground equipment. Taking the time to locate and mark underground systems prevents accidents that occur when someone using digging equipment cuts into their own equipment, or a wire.

Here’s what you need to know:

- Keep padmounted transformers free of vegetation.

- Call WEC if your padmount transformer is unlocked or looks like it needs maintenance.

- Call 811 (DigSafe) to mark utility-owned equipment.

- Hire an underground locating company to locate and mark non-utility facilities and equipment.

Changing gears: after my Safety Minute on generator safety (October-November 2024), I received a letter from member Stuart Granoff. He had just bought a generator, and wanted to know if the less expensive interlock was a better option than a transfer switch.

Here’s a synopsis of my response:

First, if you install a transfer switch: I trust that any licensed electrician (Journeyman or Master Electrician) can safely install a transfer switch to eliminate the potential for backfeeding the lines. The State maintains a database of licensed electricians.

And yes, the inexpensive interlock can be used instead of an expensive transfer switch. However: the connection depends on the kind of generator you have, and the decision really depends on the owner. The interlock takes more owner involvement and understanding of electric systems. And unlike some transfer switches, it is not automatic. The interlock physically allows only one breaker to feed the circuits in the house, either utility service (main breaker) or emergency generator (auxiliary breaker). If using an interlock, I recommend you have a strong understanding of home electrical systems, and build out a system to slowly warm up the generator and add back critical load.

Thank you to Stuart for writing in. I love talking with members about electrical safety: please contact me anytime with your questions, feedback, or to request a presentation.

Full link to State database of currently licensed electricians in Vermont: https://data.vermont.gov/Government/DFS-Licensing-MasterList/cy8e-89cz/data_preview

Why You Can’t Post On Poles – December 2024

Poles are an essential part of electric utility infrastructure, and all utilities take the time to monitor our poles and wires. A good number of WEC poles are accessible by road, but as many members know, we have a lot of poles and wires that travel through fields and forests to bring members power in some of the most rural parts of Vermont.

Not long ago, I was “walking the lines,” which is a utility term for performing visual safety inspections on foot, and noticed a deer stand attached to a WEC pole, just like it was a tree. To the landowner’s credit, it was removed quickly after I called it to their attention.

I can understand the appeal of using a utility pole for personal use. They’re sturdy and convenient. I have seen poles with all kinds of unauthorized attachments, including satellite TV antennae and home security cameras. I have seen landowners substitute utility poles for fence posts and mount barbed wire and electric fencing to them. Of course, we’ve all seen yard sale signs, found or missing pet signs, posted land notices, and other flyers stapled to poles.

None of these are a good idea. Attaching anything to a utility pole is a violation of Vermont law, as well as the National Electric Safety Code. That goes for even a stapled notice.

The reason is because any unauthorized attachment poses a hazard to lineworkers. Lineworkers wear rubber gloves to climb poles. Staples and push pins puncture rubber very easily, and a punctured glove exposes lineworkers’ hands to the elements, and worse, to electric shock. Staples and pins also catch on lineworkers’ boots as they are climbing and can cause them to slip, or make it more difficult to get a grip with their climbing hooks. Lineworkers also climb with a harness. When there’s anything on or around the pole, they have to transfer the harness over it. It’s hard enough to climb a pole, but it’s harder when lineworkers have to move that very heavy belt over objects sticking out of the pole that are not supposed to be there.

Poles may cross private land, and that land does belong to whoever owns it. But utility poles are owned by the utility—in WEC’s case, cooperatively owned by the membership—and nobody, including the landowner, can attach anything to poles without authorization. Rules like this are strictly for safety reasons.

Similarly, landowners can access the right of way—the land directly underneath and extending 20-50 feet to either side of the poles and wires. It’s their land. But the easement given to WEC allows line crews to access rights of way in order to service the line, and we have design specifications we must follow that do not allow anything too close to the wires.

So it pays to think twice and examine the right of way before putting anything in that area. Stacked wood, brush piles, gardens, trees, vehicle or boat storage, or even a storage shed or tiny home built in the right of way: these are all likely to pose a problem sooner or later.

Here’s what you need to know:

- Don’t attach anything to utility poles.

- Unauthorized attachments to poles make lineworkers’ jobs more difficult and dangerous.

- Store objects and debris far from rights of way.

And a reminder: Out of respect to landowners whose properties WEC accesses to service our lines, and in line with our environmental mission, WEC crews don’t use herbicides in our right-of-way vegetation management.

Members can recommend Safety Minute topics and request safety presentations from David Young for their school, organization, or community group. Contact him at 802-224-2340 or david.young@wec.coop.

Safety Minute: Generator Safety and Winter Prep Tips

Electrical safety tips from Safety and Environmental Compliance Specialist David Young

As winter storm season approaches, it’s time to prioritize preparing for outages, and keeping safe during outages. This Safety Minute, we’ll build out a sequence of safety activities you can do quickly along with your regular chores.

Generators are useful for providing power during outages, and for some households, they are lifesavers. But they need to be installed and operated safely. The combustion engine in generators poses health and safety risks, and generators can backfeed power to lines and hurt lineworkers. If you have a permanent standby generator, those should have safeguards to prevent most of these issues. But if you have the kind of generator you haul out of the garage or barn when a storm is coming, keep safety top of mind.

Make sure you have plenty of gas for your generator, and replace it before the winter storm season. Non-ethanol gas is worth the premium price, if you can locate it. Ensure the nozzles on your gas cans fit tightly, and replace them if necessary.

Standby generators exercise themselves every week or so. You can keep your portable generator in similar good shape by running it for five to ten minutes every other week. At the same time, go check the batteries in your carbon monoxide detectors and smoke alarms, and sweep out vents in your dryer, pellet stove, and other vented devices in your household.

If you buy water in plastic jugs, check the expiration date. Plastic breaks down over time and leaches an unpleasant flavor into the water. Store water in glass or ceramic jugs, or replace your plastic water jugs. You can always use the old water as backup for flushing your toilet.

A nifty tip is to find a flashlight that’s compatible with your rechargeable tool batteries. These lights are powerful, and much better for the environment than those that use disposable batteries. While you’re doing your safety chores, check your tool batteries and recharge any that are low. These will be valuable for your flashlight in a long outage.

So here’s your checklist:

- Check your gas and replace gas and tank nozzles if leaky

- Run your generator for 5-10 minutes

- Check CO and smoke alarm batteries

- Sweep vents

- Check or replace water

- Rotate or recharge tool batteries

In less than ten minutes, you’ve done an important safety service for your household.

During an outage

Even with carbon monoxide alarms, the CDC says 400 Americans still die from unintentional CO poisoning each year. Never run a generator inside a building, including garages: make sure it’s a minimum of 20 feet away, and point the exhaust away from any structure.

Monitor your generator’s gas consumption. A hot generator can ignite gas vapors. If you need to refill it, shut it off early in the day, wait for it to cool, and refill it while you still have daylight.

Backfeed prevention

Many people will use extension cords to plug one or two essential devices, like a freezer, directly into the generator. If you’re using a generator to power your whole house, the right way to do it is to isolate your house from the grid. If your home is connected to the grid and you’re powering it with a generator, that electricity can flow onto the line: it’s called backfeeding. The national electrical code requires that you have a system to prevent backfeeding. The reason is because when lineworkers are repairing the line, any electricity on the lines can be very dangerous.

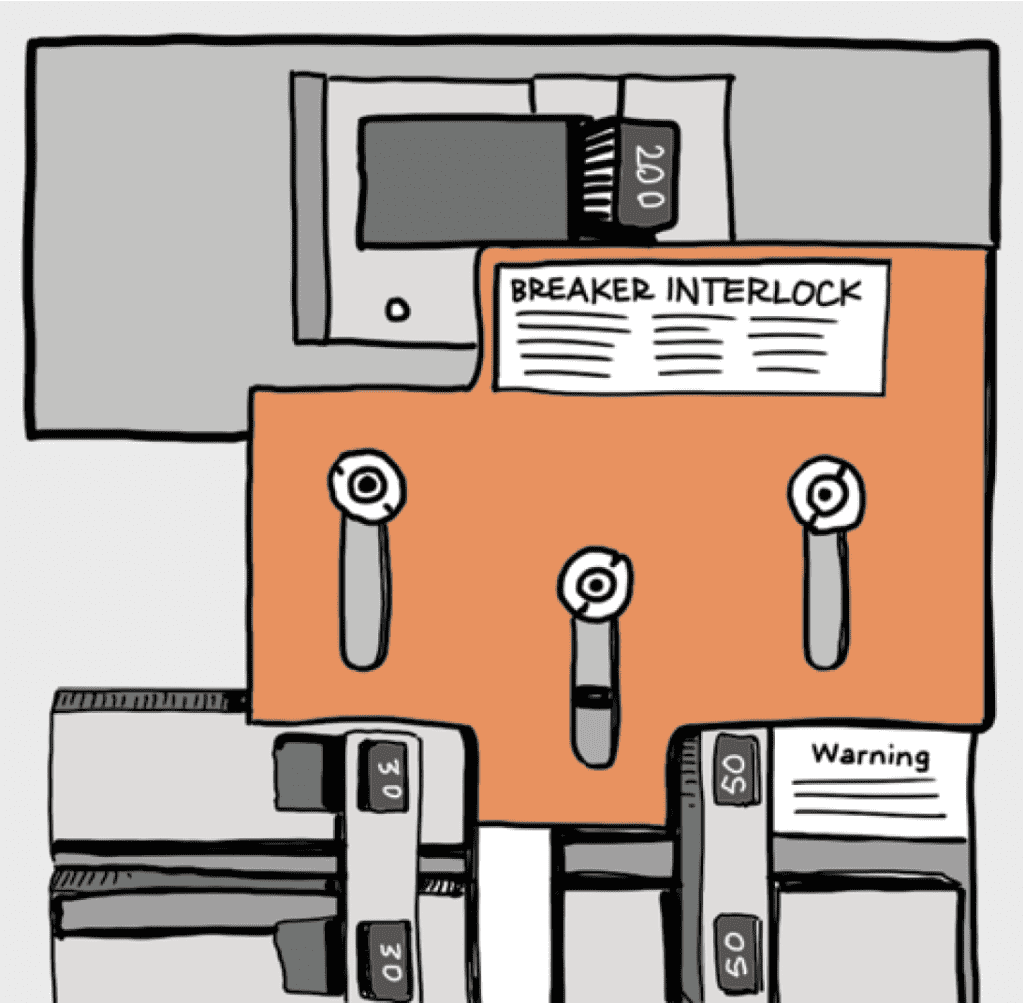

This illustration [by Tim Newcomb] shows a manual interlock option I like: it goes in your service entrance box, or breaker box, over your main breaker. Instead of a thousand dollar transfer switch, you can buy an interlock for about $60, plus the cost of a licensed electrician to install a new breaker for your generator and the plug-in spot to your service entrance.

The interlock will only allow the generator breaker to be switched on if your main breaker is off, and will only allow the main breaker to turn on if the generator breaker is off. So it allows you to toggle safely to generator power and back to utility power without risk of backfeeding the lines. Look for a generator breaker interlock kit that will work with your system.

Members can recommend Safety Minute topics and request safety presentations from David Young for their school, organization, or community group. Contact him at 802-224-2340 or david.young@wec.coop.

Safety Minute: GFCI Outlets

Electrical safety tips from Safety and Environmental Compliance Specialist David Young

One of our members, Richard Scheibner from Calais, reached out to me about our recent Safety Minute on outlet safety. He enjoyed the topic and had some great feedback. In that column, I discussed the temperature of outlets: warmth can be a possible indicator of damage. Richard and I had a great conversation, and he added an interesting point about GFCIs (Ground Fault Circuit Interrupters). He noted that they usually emit some heat. That’s true, and it’s not due to damage. Here’s why these outlets are slightly warm, and why they are important.

A properly functioning GFCI might feel warm because there is a small circuit within it, and also a small light. The circuit’s job is to compare the power going out of the outlet to the power coming back into the outlet. If everything is working correctly, these should be identical.

But if the current going out doesn’t match what’s coming back, the GFCI assumes the electricity is taking an alternate path, which could be dangerous. This could mean there’s a problem with an appliance, like a toaster: perhaps the electricity is misdirected to the toaster case, which becomes a fire hazard. At worst, it could mean the electricity is traveling through a person. That’s why the GFCI trips off: it’s a crucial safety feature preventing electric current from going where it shouldn’t.

The National Electrical Code specifies where GFCIs should be installed, originally focusing on damp or wet locations like garages, outdoor areas, kitchens, laundry rooms, and basements. Over time, the recommendation has expanded to include more areas of the house. While this is great for safety, it can lead to nuisance trips, turning off something you really don’t want turned off, like a refrigerator or freezer.

When I got my electrician license in 2012, GFCIs were not required everywhere. Now, the code suggests having them throughout the house. It’s not mandatory if your home met the code when it was built, but it’s a relatively inexpensive upgrade, and it’s smart. Upgrading is a proactive way to improve safety, and hiring an electrician is often the best route to ensure everything is done correctly and safely.

Here’s what you need to know:

- GFCI outlets emit some heat because of their internal circuit. The heat is not an indicator of damage.

- The National Electrical Code now requires installing GFCIs in all damp areas of the house, but only requires this for new buildings. The only areas not affected are bedrooms, living rooms, and dining rooms on the main floor. If those areas are in a basement, it is considered a damp area and must have GFCI protected circuits.

- Upgrading outlets to GFCI is a fairly inexpensive upgrade, and particularly important in damp areas.

I appreciate Richard for contacting me to offer his insights. If you have any questions, please reach out. I value conversations with members, and your questions and suggestions for future Safety Minute columns.Members can recommend Safety Minute topics and request safety presentations from David Young for their school, organization, or community group. Contact him at 802-224-2340 or david.young@wec.coop.

Safety Minute: Preventing House Fires 2—Cord and Appliance Safety

Electrical safety tips from Safety and Environmental Compliance Specialist David Young

In the last Safety Minute, we discussed preventing home electrical outlets from becoming heat sources. In this issue, we’re focusing not on the wiring in your walls, but on what you plug into outlets.

I have family members who experienced a house fire because of a dehumidifier plugged into an outlet with an extension cord. The extension cord had a rug placed over it to prevent the cord from becoming a tripping hazard. However, the rug held in the heat of the extension cord, which started the fire.

In that case, part of the issue may have been with the cord itself. When you use an extension cord, it needs to be clear of anything that could trap heat, and it needs to be the right size for the job. White or brown indoor cords are fine for a lamp, but they’re not appropriate for a heavy electric load. For powerful devices, and certainly for any outdoor use, you need to use a cord rated for that purpose.

There are two other common electric causes of house fires. The first is electric heating appliances. Heating appliances must be installed and serviced correctly, clear of combustible items. It is a good practice to vacuum dust off from heaters and inspect wiring. Wood or pellet stoves need to be serviced at least annually and the stove pipe needs to be clear.

The second is often overlooked: dryer vents. If you use a clothes dryer, keep your lint traps clear, and for the lint that inevitably gets stuck anyway, you can use a big brush that looks like a bottle brush to clear it out. I know a few people who bring their battery powered leaf blowers in the house and use those to blast the lint out of the dryer vent.

Here’s what you need to know:

- Inspect your extension cords before you use them and make sure you’re using one suitable for the energy you’ll be using. If you’re using one outside, make sure it’s intended for outside use.

- Don’t put anything that could catch on fire over a wire or heat source.

- Make sure wood stoves, pellet stoves, furnaces, and other heat sources are professionally serviced at least annually. Most people wait until fall, so for the best availability, schedule your service around May.

Members can request safety presentations from David Young for their school, organization, or community group. Contact him at 802-224-2340 or david.young@wec.coop.

Safety Minute: Preventing House Fires 1—Outlet Safety

Electrical safety tips from Safety and Environmental Compliance Specialist David Young

House fires used to be a lot more common than they are today. There are three things a fire needs: fuel, air, and a heat source. Oil lamps and candles were the heat sources that caused most house fires, so buildings in WEC’s service area became much safer in 1939 onward, as they were wired for electric light. However, electricity can still cause fires when wires are misinstalled or when electrical connections are loose. You do not want your electric wiring to become a heat source.

In Vermont, individuals can wire their own home with no experience other than watching a Youtube tutorial. Home inspectors make sure everything is wired correctly–which is an important reason inspection is usually a condition of selling or buying a home. But even in a properly wired home, tune in to your outlets.

If you have outlets you use a lot, they loosen over time. Let’s say you have a crockpot on your counter that you regularly plug in to the same outlet. After ten or so years of high use, there won’t be much tension left in the outlet, and you’ll be able to tell when you can pull out the plug with no effort. A new outlet has quite a bit of grip on the prongs. That tight connection to the wire keeps the wire cooler. If there’s a lot of wiggle, heat can build up, which melts the insulation on the wire. An outlet is stapled to a stud or the wood in your wall, so you’ve got something getting really hot, the heat goes to the wood. Wood releases a gas, and gas is flammable.

If you want to check the tension in your outlets, there’s a tool that retails for about $80. Or, you could purchase a brand new outlet–they are inexpensive–and take it around your house comparing its tension with all your other outlets.

Here’s what you need to know:

- If you go to unplug something and it feels warm, there may be an issue. The heat can be from heavy use, or it’s indication the outlet needs to be replaced. If it unplugs really easily, that’s an indication the outlet is the likely culprit.

- If you identify any loose outlets, hire a licensed electrician to replace them for you. This should not be a high-cost service.

- Keep space heaters away from walls and flammable items. If the cord feels warm, it’s an indication there may be an electrical issue.

Members can request safety presentations from David Young for their school, organization, or community group. Contact him at 802-224-2340 or david.young@wec.coop.

Electrical safety tips from Safety and Environmental Compliance Specialist David Young

Safety Minute: Vehicle Accidents

A utility pole may carry telephone cables, fiber optic cables, and at the top of the pole, electric transmission and/or distribution lines. The auger first caught a telephone cable. The cable has a steel cable in it, which pushed up the auger. The pole held two different electric circuits: transmission and distribution. The auger shorted out a total of seven wires and the pole broke

The driver heard a pop and stopped the truck. At first he thought he hit a tree, so he climbed out of the truck before he realized the electric wires were down. Luckily, our protective equipment shut off the lines. If one of the circuits had stayed energized, the vehicle might have become energized. If he had touched the vehicle and the ground at the same time, he might have been electrocuted.

This kind of accident happens with excavators, dump trucks, passenger vehicles running into poles, or when individuals cut trees that fall on the line. Here’s what to do if you are in a vehicle and there is damage to electric wires:

- Do not leave the vehicle. Call for help.

- If you are a witness, do not approach the vehicle. Stay more than 50 feet away. Encourage anyone inside to stay in the vehicle. Call emergency services.

- If the vehicle becomes engulfed in flames, jump – do not step – clear of the vehicle. When you are in the vehicle, you are like a bird on a wire. If the vehicle is energized and you touch the vehicle and the ground at the same time, your body will become a circuit for electricity.

- If you must jump clear of the vehicle, shuffle until you are more than 50 feet away. The ground may also be energized. Breaking and reintroducing contact with the ground by stepping will make your body a circuit.

Members can request safety presentations from David Young for their school, organization, or community group. Contact him at 802-224-2340 or david.young@wec.coop.

Electrical safety tips from Safety and Environmental Compliance Specialist David Young

Safety Minute: Preventing Electrical Hazards in a Wet Basement

The July floods inundated many Vermont basements with feet of water and mud. Even when there’s not historic flooding, many basements tend to get damp or wet during rainy seasons and the spring thaw.

The problem is, basements flood, and electrical panels and electrical equipment are often stored in the basement. The combination of electricity and water can damage your equipment and is dangerous. Specifically, being wet lowers the resistance of the human body to electric shock, and increases the likelihood of injury.

First, if you see any water at all in the basement, be cautious. Wear shoes so your feet do not become the path of a current. Rubber boots are ideal.

If you have an underground installation, sometimes water will enter the house through the electric conduit. The wires are insulated, but even if the conduit is glued, water can get in and goes to the lowest point: your basement. Don’t touch the wires, and don’t touch any water seeping below them.

If there’s water in your basement and it doesn’t reach the level of your electrical equipment – that’s anything plugged in, including your furnace – your equipment should be okay. If the water is rising, take the precaution of shutting off your electrical equipment. If you shut off the power, some equipment may still be functional after it dries, even if it was completely submerged.

So what do you do if you can’t safely reach your breaker box to shut off power to the electrical equipment in your basement?

If you need to quickly shut off power to your full house, there’s a plan B. You may have an external breaker, and it’s designed for homeowners to switch off and on. Here’s where to look:

- If your service entrance comes to a meter socket outside your house, look underneath for a breaker.

- If your service entrance is underground, look out at your pole for your breaker.

- Sometimes the breaker is on a pedestal – a short pole with a meter and breaker on it – in between your pole and your house.

Here’s your safety checklist:

- Plan ahead. Go down to your basement and take a quick scan of the equipment you have down there. Think about what you can and can’t move, and what might need to be unplugged. Locate your external breaker.

- If you can, install a sump pump. Make sure the control panel is well above any expected flood level. If you already have a pump, make sure it works.

- When your basement is wet, put on rubber boots or shoes before entering it. Don’t touch any wires.

- If water is likely to submerge your equipment, shut off electrical equipment that you can’t move or raise higher.

- If you need to shut off equipment and can’t get to your breaker box safely, shut off power to your house via your external breaker.

Members can request safety presentations from David Young for their school, organization, or community group. Contact him at 802-224-2340 or david.young@wec.coop.

Safety Minute: Don’t become the path for an electric current

Safety Minute is a new, regular feature from Safety and Environmental Compliance Specialist David Young. Young started at WEC in 2022 after 19 years at Vermont Electric Cooperative. He’s specialized in safety for nine years. WEC, which has received multiple awards for its safety record, is a great fit for Young, who’s enthusiastic not just about preserving the safety of WEC workers and contractors but also educating members. Young lives in Johnson and is the father of four active kids: he’s involved in youth sports year-round.

Members can request safety presentations from Young for their school, organization, or community group. Contact him at 802-224-2340 or david.young@wec.coop.

Early this spring, two individuals were working on a Saturday to cut down an enormous pine tree. Part of the tree fell on WEC power lines.

The line tripped off twice – that’s a standard safety measure – but it ended up reenergizing. Even if it seems that the power is out, it is possible for a dangerous potential to remain in the wires. The broken wires, arcing on the ground, started a brush fire, and the current turned the sand in the right-of-way to glass.

This happened at a time that our region was at high fire risk. One member went to get a fire extinguisher with the aim of putting out the brush fire. When lineworkers arrived to shut off the line, the individual was operating the fire extinguisher 15 feet away from the energized and arcing wires. That’s dangerously close.

This story could have easily had a tragic ending. Fortunately, no one was injured, and no catastrophic damage was caused.

- Don’t go within 50 feet of a downed power line. Always assume that a downed line is energized. That energy is seeking a path, and that path could be you. There’s voltage in the ground that can cross from one leg to the other. This is called “step potential.”

- If an object is touching a power line, do not approach it. Call WEC. A tree has enough moisture and mineral content to conduct electricity. If you touch it, the high voltage could pass through you. This is called “touch potential.”

- If a fire starts due to a downed power line, call the fire department, and then the utility as soon as you can.